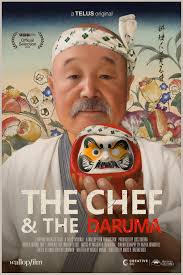

VIFF 2024 Review: The Chef & The Daruma

A documentary about Japanese-Canadian life by Mads K. Baekkevold ft. Hidekazu Tojo

Last week, by chance while waiting for another film, I saw a small crowd gather for the 2024 documentary The Chef & The Daruma. This is a film by director Mads. K. Baekkevold starring TOJO Hidekazu, the famous Japanese-Canadian chef who arguably invented the California roll, which he called the “inside-out roll” (because Mr Tojo hid the seaweed — to which North American diners were unaccustomed — “inside” a sushi roll of avocado, cooked crab, and mayo). The premise seemed too good to pass up, and upon reaching home I opened up the screener that the festival organizers had kindly provided.

It was a blast. The structural conceit of the film — which I find clever — was the use of the Daruma wishing doll as the unifying element. In the beginning of the film, Mr Tojo explains that it serves as a reminder of ganbaru (頑張る, lit. 'stand firm'), or our ability to persevere and work hard. One is tempted to agree. There are six steps to using a Daruma doll:

-

Acquire a Daruma doll

-

Set a goal or make a wish

-

Fill in one eye

-

Place the doll in a visible location

-

Work toward your goal

-

Fill in the second eye, upon success or fulfillment

Here, filling in the first eye symbolizes the beginning of your journey toward your goal, while filling in the second shows its completion. Keeping the doll in a visible location in the interim helps remind you of your goal and to keep working. In this sense, the Daruma is an union of the metaphysical with the pragmatic, of keeping up one’s earthly efforts while being open to external help.

This is a pretty good backdrop to the story of the chef himself, TOJO Hidekazu. Growing up in a poor rural family in Kagoshima prefecture with seven siblings, chef Tojo went to the big city (Osaka) upong finishing high school and trained in the refined omakase style — à la carte dining — at Ohnaya, a redoubt of haute cuisine. He recalled how he — along with the rest of the apprentices (there were ten) — slept in the tea room, doing chores that no one else wanted to so, in order to please the chefs and acquire the skills they needed. Perhaps this was where he first intuited the need for the Daruma-spirit in a culinary career, or perhaps it was even earlier, growing up in a large household where feeding everyone was a priority.

Regardless, by 1971 he was in Vancouver, working for a Japanese restaurant (Maneki) in Japantown on the Downtown Eastside. This was the fourth or fifth Japanese restaurant to open in the city, especially after the traumatic internment of Japanese-Canadians during the Second World War. The timing was fortuitous: in 1967, Canada had re-opened immigration to all races and origins, including from Japan. A wave of Shin Issei (lit. ‘new first generation’) or “New Japanese” arrived on its shores, and brought with them demand for authentic tastes of home. Mr. Tojo was hired to be a sushi bar chef, but proved to be much more. Moving to another Japanese restaurant where he did traditional Japanese haute cuisine, he eventually opened his own restaurant, Tojo’s. It was located on booming West Broadway where it still is today.

That’s where he began experimenting with new ingredients and styles, having the freedom to operate in his own space. He noted that Canadians refused to eat raw fish, and found seaweed disconcerting. So he innovated. He mixed cooked crab with mayo and put the seaweed on the inside of the roll rather than outside, hence the the name “inside-out roll.” It took off, especially with the growing popularity of Japanese culture in the 80’s and eventually, Expo ‘86. He became a celebrity chef, frequented by such guests as Tom Cruise and other Hollywood luminaries.

All along, the chef had kept to his original premise. He wasn’t just looking for commercial success, although he began with it. It was, like the Daruma itself, iterative. As one wish is fulfilled, you begin another. Near the end of the film, he was engaged in dialogue with a new Japanese chef (Harada) in Kyoto, who had begun making dashi — a Japanese stock — without seasoning. Mr Tojo praised its strong and clear flavour, but he liked even more the chef’s willingness to innovate. Like Tojo’s itself, it is a story of seeking new heights from humble beginnings — one that is still unfolding.

S.F.