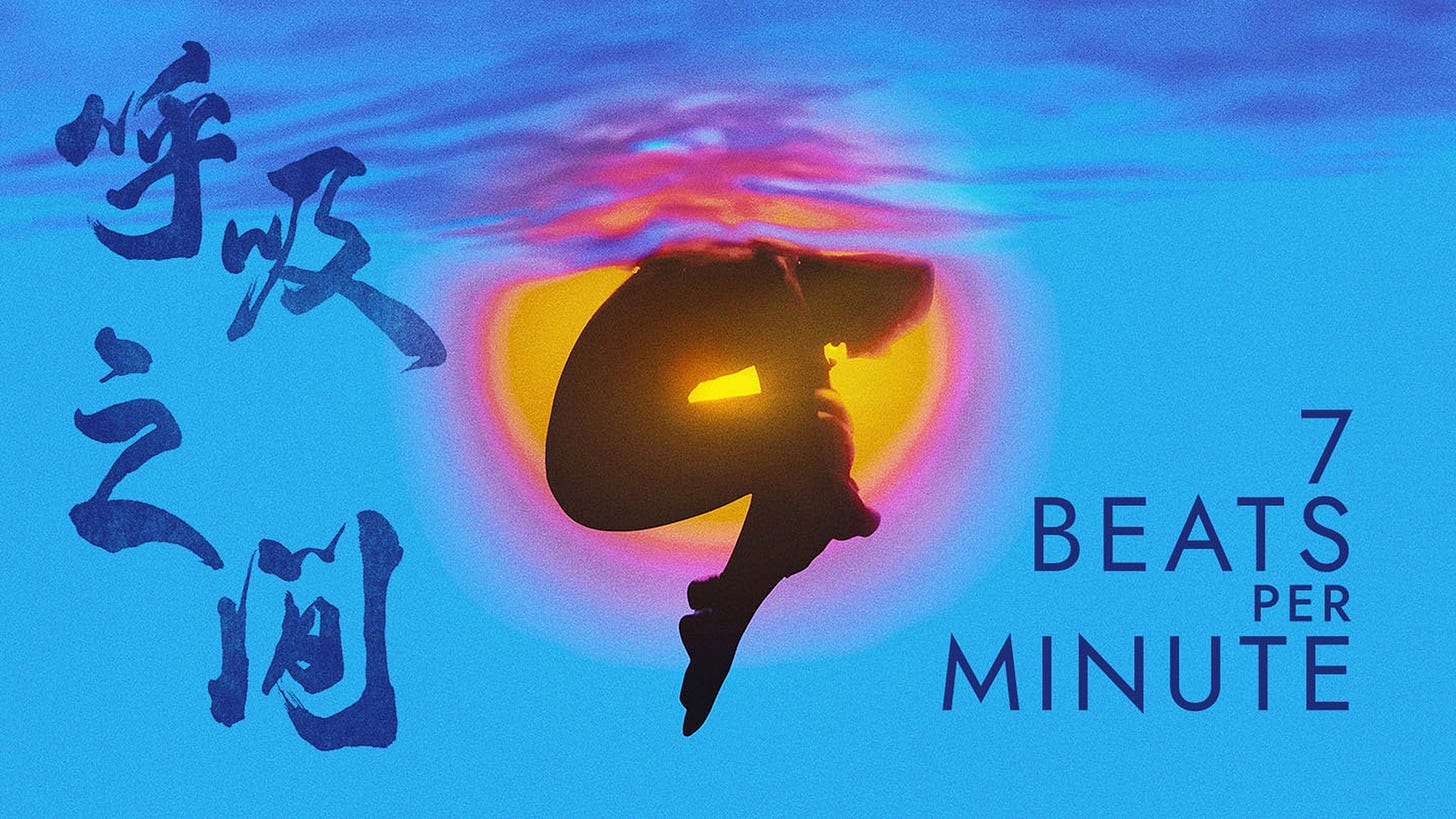

VIFF 2024 Interview: Yuqi Kang, director of 7 Beat per Minute

7 Beats per Minute will have a theatrical releases this winter. Dates to be announced, but the best way to find news about the release is to follow the National Film Board on Twitter at @thenfb.

Transcript

STEVEN: Just to start, please tell us a little bit about yourself, what you do, what your passions are. And a little bit about your film [7 Beats per Minute].

YUQI: My focus is primarily on documentaries. That's how I got introduced into filmmaking. I went to a program in New York called Social Documentary Film. And initially, what got me interested were you know, stories outside of my own life, different cultures and different people. The current project, 7 Beats Per Minute, features the Chinese champion freediver, Jessea Lu. In 2018, at one of the world-record attempted dives, she had a terrible accident and almost killed herself. So ever since then, it's been her journey coming back to the place where she almost died.

STEVEN: And what do you think makes the moment, the subject matter, and the character compelling?

YUQI: I mean, Jessea graduated from Peking University. I don't know if you know much about China and the universities there. For someone who's able to go to Peking U or Tsinghua, it's really rare and very difficult. So, even just her professional accomplishment is pretty astonishing. And let alone with all the academic and professional achievements, she's also a freediving world champion. Which is so... polar opposite from what she does in her professional field. And free diving is a very dangerous sport. With every dive, there's a possibility that she will never come out of the water. And these extreme 2 contrasts in her life were really interesting to me, already. And then she experienced a near-death experience; and then the spiritual journey she experienced was very compelling to me.

STEVEN: This is an interesting discussion because I was watching the Paris Olympics this year, and one of the runners, track & field runners on the Chinese team – I think it was the relay – someone from that was from Tongji Medical University in Shanghai, one of the top schools in China. And he was also an Olympic track & field athlete. Incredible.

And it’s not something you could have imagined 10 years ago, even. Because back then, if you were in the athletic system, or artistic system, you weren’t doing normal school. You were doing what was called “cultural education,” basically remedial. I grew up playing piano, and my teacher was a professor at Shanghai Conservatory. She was director of a piano. And she was like saying, yeah, you know, like, if you were like on that path, like whether it's athletics or music or something else, you wouldn't really be doing normal school, right? And so like, it's a very different path.

And it's fascinating because it's a great angle; because it shows it's not just one person's spiritual journey – although it is most importantly that – it also shows the path of a society as a whole; all of Chinese society as it evolves right? There’s more material wealth, but even more importantly, there’s a kind of freedom in how, you know, how you live life, right? Like I had, I remember, you know, I had a nanny growing up. I'm from central China. She’s from the villages, the countryside, of course. And she was telling me, telling us [the family] – when they left the countryside to go work in the city, their original goal was to just kind of make enough money to come back and raise a family. And as your position in society changes, your desires change, what you want out of life changes, your relationship to society changes. So I think in the case of events such as this, it's one person's struggle clearly; but it’s also a refraction and reflection of the wider social themes right?

YUQI: [nods]

STEVEN: What was the thing that surprised you the most when you went through this journey of talking to Jessea?

YUQI: Yeah, so I met her in the middle of 2019. And I was supposed to follow her through the next cycles of training in 2020, when you know the pandemic broke out, and the whole world shut down. And so overall, like, this has been a seven-year project.

I’ve really gotten to know her. Every year, I would go to her house, do some filming, catch up, and see what she's been doing at the time. We sort of grew up together, you know; spending five, six years revisiting each other and talking about many things. The most surprising element for me and for many other people: you know, she's a graduate from Peking University. She has a PhD in pharmaceuticals [pharmacology], a well-paid job in the U.S. She bought her own house in Hawaii. She seems like she’s doing so well and she is a world champion. And people automatically assume she has it all figured out. That she's living the dream life. But what I've really learned about Jessea is how vulnerable she is and how much she's struggling with her own mental health and struggling with the demons coming from her childhood.

And that just goes to show even somebody with a lot of external accomplishments, it's still very much the same as most people. They struggle with day-to-day life. They struggle to find the connections and struggle to be vulnerable with people. So that was the most surprising discovery – slowly, slowly learning who she is. She's hyper-independent. She's very skillful. She manages her life really well, yet she’s very vulnerable and she wants to connect, but finding it very hard to connect with other people.

STEVEN: Right. I know what you mean, although not to the same degree. I went to a very academically competitive high school, wanted to do all these things, and I graduated into the world post-GFC [Global Financial Crisis]. I have a good job and everything, but you know, there’s this book called The Undoing Project which is about two Israeli psychologists and how people cope with loss and regret. And the key points are, do you go back to the point at which the accident / thing happened? Or when you got in the path that led to the thing? Or even the very beginning. It’s hard to say. If you can re-do a part of your life, like, what's the point to which people go back to?

But you are haunted by it to some extent. Not very much anymore for me, but I can understand it. And if it is imaginable to me, I am sure it’s even more so for someone who was at the top of her game and have to live with something – which happened in the blink of an eye – for the rest of her life. Looking forward, what kinds of projects are you interested in exploring? What kinds of projects are you engaged in?

YUQI: I generally choose projects that I'm most interested in, like subjects I’m most interested in at the time, to pursue. And what's the nature of filmmaking? Like even the fastest film you will spend 2, 3, 4, 5 years with it. So I have to be deeply passionate about the subject matter because a portion of my life will be dedicated to it. My first ever film was about, you know, a 5-year-old orphan, a Tibetan monk, living in Lumbini. That was about a little child, you know, seeing how he dealt with the monastic environment. And this one is about freediving. But what drew me into both is, I think, my own existential crisis.

I think like as a young kid, I always had this wonder, you know, why am I here? What does it mean to be human? All this, it always confused me. And when I was a teenager, my grandma passed away. That again shocked me because she's laying there, but her soul went somewhere else. Where did her soul go, you know? So I developed a strong interest in religion. So naturally, when I started to pursue a career in documentary filmmaking, I went to the most religious place to learn more about religion.

And jumping from that film, the 2nd film, you know, I read books about the deep sea and human life origins, which is believed, you know, long before current life on Earth right now, walking, running, flying, originated from the salt water, the ocean. That's what really drew me into these subject matters. And I think if I was going to do another documentary, it will be about spirituality again.

STEVEN: That's really interesting, because I was very interested in spirituality, at some point in my university career. Not as cosmic, less of where I am here, more like where am I going? You know, what’s the next step? I wasn't very interested in the real world. I wasn't very interested in careers, jobs, all that stuff. I knew I didn’t want to get a PhD. My mum obviously was interested in my getting a real-world job. Getting on with my life. That kind of thing.

But I was kind of like, what's my place in the world? What's my relationship to society? I started reading some ancient philosophy, like Aristotle, that kind of thing. But I also started reading some medieval religious commentary on it as well. You know, St Thomas Aquinas, commenting on Nicomachean Ethics. And that went on for a while. I don't think I ever got any firm answers out of it. And I think that’s pretty common, no firm answers. To shift gears a bit, what opinion of yours, what idea of yours got changed as a process of doing this movie or other movies?

YUQI: I think coming from a traditional background, learning documentary filmmaking from academic institutions, one thing to understand is that the ethics when approaching a person or subject matter is not always black and white. In terms of following Jessea's life for a long time, I just tried to set up a wall as a passive observer, who has a camera to record her life. Not to try and interfere or say anything, because I am filming. Not to impact her life or change its course in any way.

Ultimately after a few years, I realized my following her, and her letting me film, we're mutually affecting each other, and perhaps directed our own life choices to different directions. I no longer can hold to the position of just staying behind the camera as a passive observer. I have to step into Jessea's story and understand that my role being a storyteller following her life has changed the course of her life, her decisions, and understanding we're mutually impacting each other. That’s a big thing coming out of this story. I feel in the future, if I ever approach another deeply character-driven story, that I work with somebody one-on-one, I wouldn't struggle as much as I did with this project. I would understand much better that the reality – when you're inserting yourself into somebody's life – these impacts will happen. And so, I am left with the responsibility as a storyteller to my audiences, but also to Jessea as an individual. What kind of impacts a story coming out would have on her own personal life as well.

STEVEN: That’s a great point to end the interview on. A film, it’s not a purely scientific activity. You can't just be behind a telescope or microscope. These are human stories, and human stories are fundamentally interactive because we're social animals. When you think about the first stories of mankind – Odyssey, Homer, Illiad – these are stories which people took part in enacting as they’re telling them. And people did some of the things they did, partly because they wanted to end up in these stories. And it reminds me – one of the greatest works of anthropology is called Argonauts of the South Pacific, by Bronislaw Malinowski. He was stuck in the Trobriand Islands basically for the entirety of the First World War. And he did essentially what you did, which is kind of participant observation. The only thing you can do is to try and do the best by your subjects. To hope that your impact will be a good one instead of a bad one. Anyways, it's been a pleasure speaking with you.

YUQI: These are very interesting conversations. Thank you so much. Bye-bye. Have a nice day.