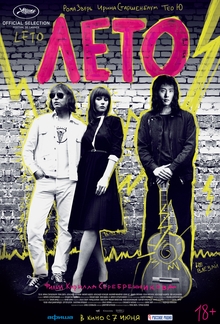

VIFF 2018 - Leto

Kirill Serebrennikov's latest feature takes us back to the USSR in an exuberant attempt at capturing a Soviet rock legend, Kino, teetering on the very cusp of stardom. The plot unfolds over a single summer in Leningrad, chronicling the youthful energy of the Soviet rock scene of the 80's through the ascent of a then-unknown Viktor Tsoi (Teo Yoo) in an imaginative, highly stylized black and white cinematography.

At its core, Leto ('Summer' in Russian) is driven by human connection. Specifically, it is driven by the triad of 19-year-old Tsoi, 26-year old rocker Mike Neubaum (played by real-life musician Roman Bilyk) and his wife Natalia (Irina Starshenbaum) in a complex, messy, and often-childish web of mentorship and desire. This is a strong cast with strong performances, the German-born Yoo in particular capturing Tsoi with uncanny resemblance and brooding nonchalance; the dubbing is so seamless that it is easy to forget that he does not in fact speak Russian. Largely speaking, Leto is also the personal history of the Leningrad Rock Club, a historical venue for Soviet rock music created with the express blessing of Leonid Brezhnev. It is within this locus in which the summer unfolds, riding the uncertain wave of then-unprecedented creative freedom in conjunction with cultural censorship.

Leto has all the quintessential elements of a biographical rock film —romance, rebellion, and rock and roll—situated within the political context of perestroika; a slow thawing summer that seem to never come fast enough. It is easy to interpret the movie as purely anti-establishment, but what takes place is more complicated. When the very minutia of bodily movement and language is disciplined under the watchful eyes of the KGB and various apparatchiks, counter-culture works contrapuntally with and against the state. At nights, musicians play underground rock shows that delve into drunken stupor. In the morning, Tsoi and his then-unnamed band audition before a commissioner to be granted legal membership to the Rock Club. Fans enjoy a slice of freedom as Neubaum performs with his band Zoopark in a music hall. These same fans are then reprimanded by the

Komosol for simply holding signs or moving too much. Serebrennikov manages to blur this contradiction rapturously, interjecting the narration with surreal, fantastical musical sequences that soar into catharsis: for a minute, the music halls, streets, and streetcars transform into bursting choral arrangements. They end wistfully, defiantly, with the repeated line to the audience: This did not happen.

There is a sense of universality to the world Serebrennikov has captured here. While this particular cultural milieu may be bound in the annals of history, the youthful energy has not been lost, in Russia and elsewhere. It is also hard to not think of the director himself, when confronted with the central theme of the struggle for creative expression; Serebrennikov has under house arrest for over a year under charges that some argue were made in retaliation for his outspoken political views. This, and the knowledge that both Tsoi and Neubaum died premature deaths, makes the triumphant ending somewhat bittersweet. But maybe here is where the irony lies: freedom resides within the art of the repressed and confined.