Tampopo at the Cinematheque

I told myself that my two teachers, both middle-aged Chinese gentlemen, were the last people I'd take to see Tampopo. I told my brother as much, and he agreed. Yet as it turned out, both my teachers accompanied me to the Cinematheque late this January to watch the new digital restoration of Tampopo on the big screen. It's a strange world where elderly Taoist disciples accept an invitation to see the only ramen-western in the world, but for them to enjoy it as thoroughly as myself? Perhaps it is only such a human film asTampopo that can draw both me and two Taoists—not to mention the rest of Vancouver—to the Cinematheque on a dark winter's night.

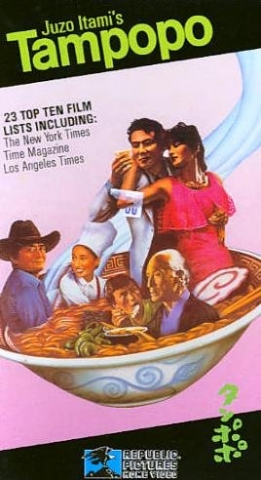

To the uninitiated, Tampopo is a cult film directed by Juzo Itami about Japanese food culture. The plot follows the story of Tampopo, a widowed mother and restaurant-owner who seeks help from Goro, a John Wayne-like trucker, and his sidekick Gun (and the rest of the gang, rounded up Seven-Samurai style) to make a perfect bowl of ramen. Sprinkled between this narrative are a series of satirical vignettes a la Jacques Tati or Luis Bunuel, including a grocery clerk chasing after an old woman obsessed with squeezing food, a lowly employee embarrassing his executives with his culinary knowledge whilst ordering from the menu, and a moribund housewife preparing a final meal for her family. Yet what notably distinguishes Tampopo from other filmic fare and earns itself a devoted cult fandom are the outlandish erotic acts featuring a fourth-wall breaking gangster and his dame. Audiences are equally thrilled as they are enticed by the faint visual pleasures of an egg-yolk employed as a sex-toy, the commingling of food and love-making, and a kiss shared after the revelation of ingesting a raw oyster. There is no other way around this fact: a major amount of Tampopo's fame is derived from this investigation into the sensual realm, for which it has gathered a cult following.

The film experience itself is, of course, infinitely more than any plain old description of the dish. Tampopo is a playful exercise in miscellaneous superlatives, a film beloved for its life-affirming qualities. Like no other film it emphasizes the underlying connection—and myriad possibilities—between gastronomic and sexual pleasure.

But these erotic segments are a side-show; it is beyond this realm, however, that I feel lies the profound beauty of Tampopo. The film is a quietly exultant celebration of time-honoured human relationships expressed through the most essential human ritual—food preparation and shared meals. The whole of the human condition is apparent in the film, and we move from the ecstatic poetry of life to the observance of death. Yet the film retains its light and humorous tone, never straying too far from its heartwarming nature. From students to sensei, adults to toddlers, ragamuffins to rich folks, the human community appears in its idiosyncratic richness, but none so splendid as the gang that helps out Tampopo in her quest to create a perfect bowl of ramen to sell. Beyond the gruff yet kindhearted trucker Goro and his frank buddy Gun are Sensei, a retired elderly gentleman sought out to help with the broth, Shohei, a noodles expert and chauffeur of a wealthy man who extends his driver's services to the team, and Pisken, a contractor and a drunkard who, along with his friends, beat up Goro at the beginning of the film. Then there is Tampopo herself, the lovable widow and enthusiastic student. There is a sincere affection to this humble community which formed to assist a woman achieve her dream, a sense of completeness which radiates outward and reminds us of the people in our own lives. Food is what keeps us together and which, amid the indignities and uncertainties in life, acknowledges our fundamental human bonds. This is what the film tells me above all else.

Excluding films like Koyaanisqatsi, Tampopo is one of those few films which I feel has a genuine universal appeal across generations and societies. It is a restorative film that nourishes and replenishes the soul with a healthy excitement in what both the ordinary and extraordinary rituals in life have to offer—whether it's a perfectly sublime bowl of ramen, or a smilingly simple rice omelette. Tampopo reminds us that food, above merely energy or habit, is as much about satiety as it is about satisfying human relationships. I confess to still being mildly puzzled as to how my Chinese teachers could so dearly enjoy this film. But this I do know: that if we live by Tampopo's effusive joie de vivre, those little parables on human relationships, then we too might find contentment amidst the tragedy of this world.